Learning from Commercial Aviation for IT Incident Management

This post explores some ways in which IT incident responders can learn from commercial aviation safety practices in handling crisis situations and emergencies, recovering from service outages and fostering resilience and continuous improvement.

TECHNOLOGY

9 min read

Introduction

I have great admiration for IT incident responders. Often under extreme pressure, and sometimes with significant lack of sleep, they must remain calm and debug complex issues to help get systems back online. At worst, these systems could be affecting critical infrastructure like a hospital, airport or a fleet of electric vehicles. As software continues to eat the world and digital connectivity becomes ever more indispensable in people’s daily lives, the information technology industry is under ever greater pressure to ensure system resiliency and robustness. Incidents like the Crowdstrike Windows shutdown of Summer 2024 highlight the fragility of IT systems that the public interact with on a daily basis. The risk to societies is only set to increase as we continue to depend more and more on internet-connected devices in our day to day lives.

The IT industry can learn a lot from the experience and maturity of commercial aviation safety and accident prevention to help drive better safety practices and be more successful in resolving critical incidents and applying the learnings for continuous improvement. In this post I will lightly touch on several areas of commercial aviation safety and accident prevention that will be of benefit to IT professionals in helping optimize incident response for business continuity and stable IT infrastructure.

Crew Resource Management - a recipe for successful team collaboration during complex high stakes incidents

Humans behave in unpredictable ways under high pressure and in crisis situations. The importance of training and preparedness for successful incident response cannot be over-stated – knowing your role and those of your peers. Having a playbook and trusting that your peers know what to do can help avoid loss of situational awareness and reduce the risk of poor human bias-induced decision-making.

The discipline of Crew Resource Management (CRM) in commercial aviation was developed out of the recognition how crucial the human factor is with respect to accident prevention. CRM emphasizes teamwork, interpersonal communication, leadership and decision-making in the cockpit and across the entire flight crew*. CRM has been credited with reducing the number of accidents not only in aviation, but also, ship handling, firefighting, and surgery, and any other activity in which people must make dangerous, time-critical decisions.

*You can find many interesting cases of aviation failures due to lack of CRM (and accidents that were prevented due to excellent CRM) here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crew_resource_management

The "Miracle on the Hudson" - US Airways Flight 1549, which made an emergency landing on the Hudson River on January 15, 2009 - is a textbook example of CRM in action. Captain Chesley "Sully" Sullenberger and First Officer Jeff Skiles faced a dire situation when their Airbus A320 struck a flock of Canada geese shortly after takeoff from LaGuardia Airport, causing both engines to fail. With only minutes to react, the crew’s response showcased how CRM principles can turn a potential disaster into a remarkable success.

Sullenberger took control of the aircraft while Skiles worked through the engine restart checklist—a clear division of tasks that avoided overlap and confusion. This workload management is a cornerstone of CRM, ensuring that each crew member focuses on their strengths in a crisis. Sullenberger’s calm, decisive communication with air traffic control and the cabin crew also reflected CRM’s emphasis on clear, concise information exchange. He famously told the tower, “We’re landing in the Hudson,” a statement that conveyed the plan without hesitation or ambiguity.

Meanwhile, the cabin crew—trained in CRM principles—prepared passengers for the water landing with remarkable efficiency. Flight attendants issued commands like “brace, brace, brace” and ensured an orderly evacuation onto the wings and life rafts once the plane settled on the river. This seamless coordination between cockpit and cabin was vital, as CRM stresses that safety isn’t just the pilots’ responsibility but a collective effort.

Sullenberger later credited CRM training for their success, noting how it equipped them to stay calm, assess options (like returning to LaGuardia or diverting to Teterboro, both deemed unfeasible), and execute a plan under extreme pressure. The outcome - 154 passengers and crew safely evacuated with no fatalities - underscored how CRM transforms individual skill into cohesive teamwork. It’s why the incident is studied in aviation training worldwide: it’s not just about Sully’s heroic piloting, but how the entire crew’s disciplined, collaborative response turned a double engine failure into a miracle.

How does this relate to IT incident management? Large organizations will typically have an Incident Management System that is leveraged during IT systems outages or data loss situations. During a major incident, an Incident Commander (IC) or Escalation Manager (EM) may be engaged. These individuals are tasked with maintaining ongoing situational oversight throughout the lifecycle of the incident. If we look through the lens of CRM for the benefit of IT incident management, the Incident Commander should be ensuring the right structure is in place with all stakeholders held to account for agreed actions. The incident commander should have the authority to assign specific duties - like one person or team handling network diagnostics while another coordinates with vendors - preventing the chaos of everyone piling onto the same problem or, worse, neglecting a critical area. All of this should be documented as part of an incident response playbook.

Another lesson from CRM is about how consistently applying protocols and decision-making framework under stress can minimise individual human biases and ultimately mistakes. Aviation crews train to avoid tunnel vision and consider all options, even in a crisis. For IT, this can mean pausing mid-incident to reassess: "Are we chasing a symptom instead of the root cause?" A structured debrief - like a quick "huddle" mid-response - could keep the team from spiraling down the wrong fix. Putting structure and maintaining team discipline during a chaotic, stressful situation is inherently difficult. This is why incident managers are often deliberately non-technical, allowing the technical SME, to keep their hands on the keyboard while addressing all of the admin tasks associated with managing the incident.

Finally, CRM helps promote situational awareness - a key concept for understanding human behaviour and preventing poor decision-making in times of stress. One of the primary reasons why we have a minimum of two pilots in a cockpit is to ensure situational awareness is maintained at all times, where one pilot flies the plane, and the other monitors the aircraft’s position, altitude, speed, weather conditions etc. Loss of situational awareness can happen due to various factors including distraction, fatigue, information overload, poor communication or misrepresentation of data. Under considerable stress, pilots may neglect their agreed roles and start inputting conflicting inputs into the flight controls. A famous examples where the loss of situational awareness resulted in a terrible tragedy is the crash of Air France 447 in 2009. While the captain was having a rest, there was a brief interruption to airspeed indications, lasting less than a minute. This threw the two on shift pilots into a state of paralyzed agitation. Through a series of increasingly misguided control inputs, they sent flight 447 plummeting towards the ocean, all the while trying desperately to understand what was wrong, only grasping too late that they themselves were the problem. They assumed the plane was over-speeding when in fact it had stalled and was plummeting to the ocean.

Once the findings from the Air France flight 447 crash came out pointing to pilot error leading to a stall, many people were quick to point fingers at the pilots for not correctly diagnosing the problem. But such an accusation ignores the fact that the pilots were systematically underprepared for the situation in which they found themselves. There were many factors at play. In such complex and high stakes situations, it is necessary to look at the underlying conditions that allowed such an error to happen in order to prevent such a situation ever arising again.

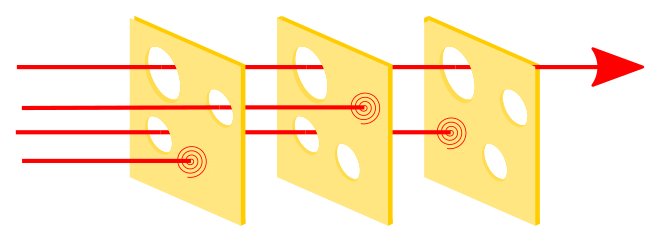

Visualizing failures of complex systems – the Swiss Cheese Model

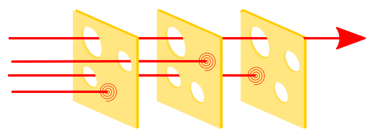

The Swiss Cheese model of accident causation likens human system defences to a series of slices of randomly-holed Swiss Cheese arranged vertically and parallel to each other with gaps in-between each slice. According to the swiss cheese model of safety, an accident happens when the holes in the stacked swiss cheese slices align, allowing a hazard to pass straight through unhindered. In the below diagram (from wikipedia), three hazard vectors are stopped by the defences, but one passes through where the "holes" are lined up.

The Swiss Cheese Model is a great way to think about IT incident investigation and root cause analysis. The model helps us understand the chain of events leading to failures within complex systems, shifting the focus from pinning blame on a single person or mistake to understanding how multiple layers of defences can fail in a complex system. The concept helps to simplify complex information and tell a story of how a sequence of failures with unfortunate timing and circumstances can have catastrophic consequences. This is an especially important part of ensuring complex information can be understood by non-specialist stakeholders and the general public.

A system crash might initially seem like "someone forgot to update the server," but the model prompts you to ask: Why wasn’t there an automated patch management system? Was the monitoring tool misconfigured? Did the team lack clear escalation procedures? By mapping out these layers—say, technology, processes, and people—you can see how multiple small failures, not just one big blunder, led to the incident. This makes the analysis more thorough and less about pointing fingers.

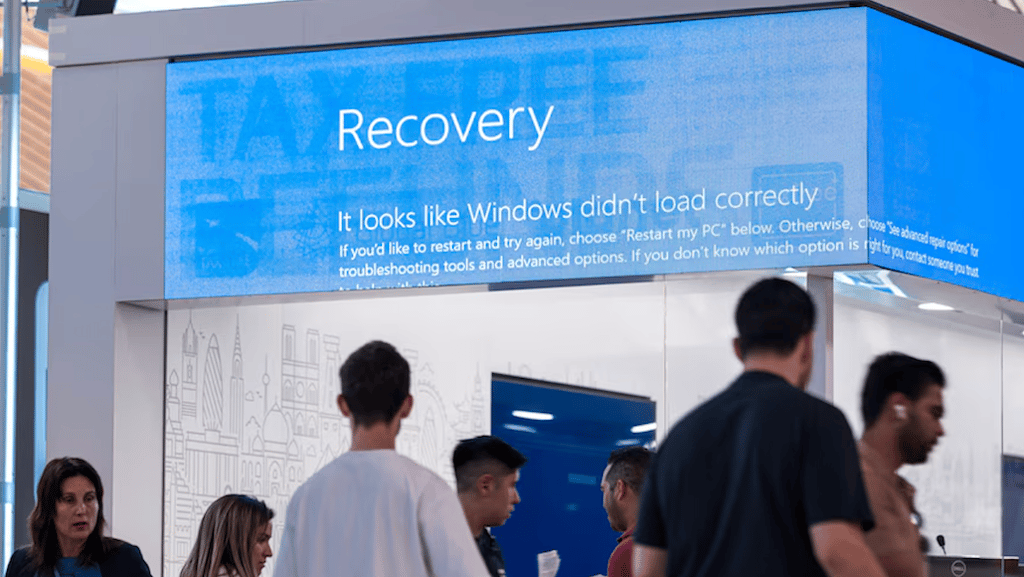

A scene from an airport during the 2024 crowdstrike meltdown where information display screens, amongst other services became unavailable due to the cascade of failures.

Conclusions

As the above examples demonstrate, there are many ways in which commercial aviation practices can benefit IT professionals tasked with ensuring business continuity of critical IT systems. Practices like CRM for incident management and and visualization techniques like the Swiss Cheese Model for root cause analysis can bring multiple benefits in terms of continuous improvement, reducing downtime and improving recovery times when accidents do happen. Of course these two examples are just scratching the surface. There are many other aspects such as data collection frameworks, having the right monitoring and logging tools and layers of redundancy in place where needed that all contribute to the stability of IT infrastructure. Looking to the future, advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and big data analytics hold the potential to further improve aviation safety and IT systems, but the human factor will always remain, and struggles between man and machine – automation and human wisdom – will forever be a challenge to overcome. Learning from human and systems failures for continuous improvement in aviation safety is another fascinating topic which I plan to return to in a separate post.

A screenshot from a "Mentor Pilot" youtube video where the pilot Petter Hörnfeldt is paying homage to the inventor of the swiss cheese model, Dr James Reason, who passed away in 2025

Let’s now take a moment to examine the infamous Crowdstrike incident of July 2024, where the healthcare and banking sectors alone had estimated losses of $1.94 billion and $1.15 billion, and tens of 1,000’s of travelers were left stranded at airports. It beggars belief that such an impact could be the result of a tiny bug in one component of a piece of security software affecting one type of computer operating system (Windows). You could list the holes in the system as follows:

An internal end-to-end test was either not done at all or wholly inadequate. The flawed security deployment process allowed a service-impacting update to affect a very large set of customers.

OS vendors like Microsoft build their operating systems in such a way that third party security solutions can assume nearly total control of the OS, which means if the third party solution fails, so does the OS.

There was no phased deployment, so everyone was impacted at once. Had the update been validated at different phases, organizations could have ensured it didn’t create service, compatibility, security, or other issues before proceeding with a larger or full rollout to all devices.

Once a solution like Crowdstrike is installed on a PC, it is able to update itself automatically, with no safeguards except those that Crowdstrike themselves choose to implement.

The considerable mess was expounded by a very lengthy recovery time compounding the affect. This also had its list of gaps. For example, an exhaustive manual effort was required to remediate most affected systems one by one - in many cases this meant dispatching IT engineers on site. Due to security protocols, many of the affected computer servers were encrypted. In order to put the servers into safe mode to fix the issue you have to release the encryption using recovery keys. Some companies had their recovery keys stored on servers already affected by same problem; hence they could not be retrieved so easily, further delaying the recovery time. All of this created an unholy mess that had to be explained to the masses of people around the globe who were affected by the service outages.