Living off the land in 19th Century Ireland

An essay comparing the indigenous Clachan settlement of the 19th century and a 'Super-rural' vision of the future from the early 21st century.

16 min read

We must abandon the idea of the city as a tightly settled and organised unit in which people, activities and riches are crowded into a very small area clearly separated from its non-urban surroundings. Every city in this region spreads out far and wide around its original nucleus; it grows amidst an irregularly colloidal mixture of rural and suburban landscapes; it melts on broad fronts with other mixtures, of somewhat similar though different texture, belonging to the suburban neighbourhoods of other cities.

Jean Gottmann: Megalopolis: The urbanized northeastern seaboard of the United States (1964)

Summary

This is a paper I wrote as part of a course I did on landscape urbanism back in 2007 that looks at a traditional Irish rural settlement form and a contemporary vision for a new rural settlement type, based on principles of sustainable development. As climate change and global pandemics continue to demand a serious re-think of urban settlement forms, this study still resonates 10 years after it was written. The paper asks the question what can we learn from the ancient settlement form in the context of contemporary spatial planning practices and the principles of landscape urbanism.

Introduction

This essay compares two ‘rural’ settlement types in Ireland. One is an existing, historic example, and the other one is a conceptual proposal. The indigenous case of the ancient Irish clachansettlement is compared with ‘Hinterland’, a contemporary design project by FKL Architects, part of the Irish entry to the 10th Venice Beinale in 2006, entitled: Sub-urban to Super-rural. Hinterland explores how a more sustainable form of settlement in Ireland might look in 2030 based on a scenario of landscape productivity combined with linear infrastructure. The two case studies are situated in the context of the ‘landscape urbanism’ movement within urban design.

Landscape Urbanism

Landscape urbanism is seen by many contemporary architects, planners and urban designers as the logical next step for urbanism to reassert itself after widely acknowledged failings of the modernist and neo-liberal periods of urban development. This is achieved by tapping in to the potential of the environment (natural and built), and taking inspiration from the permanence of landscape (in respect of human transience) as a means to give structure, authority and authenticity to a design proposal. The ‘neutral’ (or ‘neutralising’) position of landscape can be exploited as a tool, a lever, or even a starting point to prompt action, to kick-start negotiation and to resolve disputes, helping conflicting stakeholders to see the ‘bigger picture’. The approach can thus act as an important ideological tool for coping with the complexity of contested territories. Since urbanism plays a crucial role in helping translate the essence of a landscape, the genius loci, into a vision that can be embraced by society, common understanding and appreciation of the term landscape must be the starting point. Case-based analyses often provide the best means (ie empirical evidence) of reaching this goal.

The Irish context

The island of Ireland has been inhabited since 4,000BC (Bannon 1970). For 4,000 years the island remained largely pastoral, without any evidence of town-building occurring right up until the arrival of the Vikings in the 10th century. Agrarian forms of living therefore have preceded urban settlement on the island for several millennia. It is worth considering this in light of the present day Irish context of unprecedented urbanization and urban sprawl. The rate of transformation in the current physical and cultural landscape is unseen in Irish society since the since the Great Famine of 1845-49, when the population was decimated through starvation and emigration. Up until this point the predominantly dispersed rural settlement had been of a considerably high density of hamlets, small villages and scattered dwellings. The famine period left in its wake a barren, desolate landscape, and an impoverished people. Mass emigration from Ireland remained a basic fact of life right up until the late 20th century. However, by the mid 1990’s a number of factors combined to transform the Irish economy into a highly globalised service-oriented attraction pole for foreign investors. An incredible economic boom period ensued, reaching its peak right up to the global financial crisis of 2007, reversing the emigration trend, and stimulating a demand for housing that is unrivalled across Europe. The case-studies chosen for this study are representative of both the pre-famine and the present day periods. The indigenous clachan settlement was commonplace in rural Ireland up until the late 19th century; many traces still exist today. The contemporary Super-rural project of FKL Architects was borne out of a deep frustration for the consistent failure of Irish planning policy to counter the sprawl that now stretches beyond Dublin into vast expanses of the countryside, causing widespread air pollution and degradation of quality of life for commuters. By examining the two cases in this way it is hoped that some common threads will emerge and serve as a base for helping to inform the project-based discourse of landscape urbanism.

The ancient clachan settlement

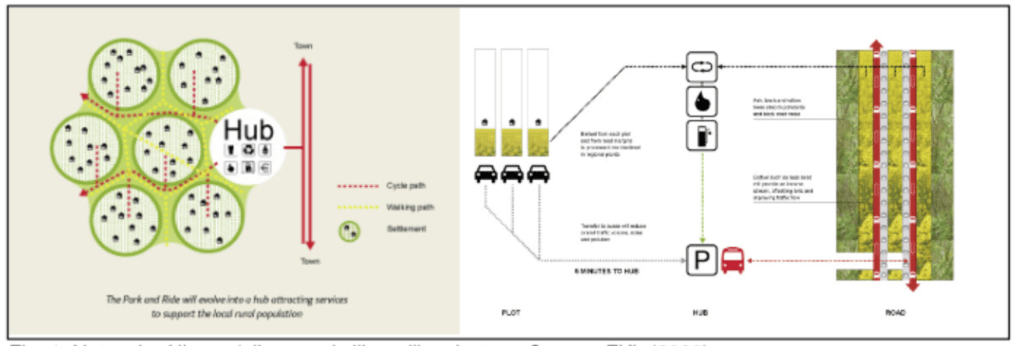

Network of linear / dispersed village-like clusters. Source: FKL (2006)

The practicalities of implementing such a radical proposal are not easy to conceive. How can the motorway, with enough planting and cultivation, become a pleasant living environment? The project proposes to subvert the motorway to public transport and the productive potential of the landscape. Surely this would require a considerable slowing down of traffic, thus reducing the economic efficiency of the road, and weakening the competitiveness of the territory. Since motorways exist to increase the efficiency of city networks, by subverting the efficiency of the network you are making a powerful statement against the city. Furthermore, by attracting people away from the city, the vitality of urban concentrations is undermined. Many people live in the sprawl not by choice but by the lack of affordable housing in the city. With lower densities the critical mass to sustain good public transport is also undermined. Such crucial issues are overlooked in the project of FKL.

Perhaps the most important issue for FKL is people’s lost association to their place of residence. Irish society has undergone a period of comprehensive modernisation. With that it must be accepted that the new super-rural dwellers would always remain suburbanites who want good access to the city. The social bonding that the new landscape productivity would apparently forge is impossible to imagine if people are still going to leave their house every morning to go to work in the city. In this sense it is very hard to visualise how such a utopian balance between an urban and a rural way of life could develop. For as long as there are cities a between urban and rural, a division between a gemeinschaft (community / local) and gesellschaft (society / cosmopolitan) mindset will always exist.

As a carefully worked out scenario and a conceptual design proposal Super-rural is deliberately abstract. It needs to be, for its aim is not to show how the ideas can be implemented but more to provoke a discussion. The aim is to visualize, in an abstract way, how an alternative future could be imagined based on the rationale of using the demand for alternative energy production to requalify and revalorise the place of land which has largely been eroded in the process of modernisation. By reasserting the place of landscape as an active element in the Irish economy, the project makes a brave statement about how the uniqueness and special qualities of the Irish territory might be preserved and reinforced.

Synthesis

The clachan as an episode in the history of settlement form can teach us a lot about where we are going and how we are to survive. The clachan was highly adaptable to the harsh climate of the most isolated parts of Ireland. We learn from the clachan about the functioning of the vernacular landscape – the conception of public, private and collective space, the use of natural and durable materials, the siting of the buildings in relation to topography, etc. The tribalistic clachan provided shared land which had its limits in the private space that is demarcated by simple structures (eg dry stone walls) of natural materials. In ‘Hinterland’ the historic attachment of the Irish people to the land is tacitly understood. At the core of the design concept there is implicit recognition of the Irish people’s attachment to land as a productive entity. In this sense there are interesting parallels to be drawn between the native, ‘organic’ ‘non-designed’ clachan and the Super-rural Hinterland concept of FKL. In ‘Hinterland’ there is evidently an appreciation for the core values and potential for learning from this:

The hinterland pattern will reconnect housing capacity with the productive potential of the land and thereby create a rich pastoral environment where the rural population is integrated visually and environmentally. A change in attitude to the construction of houses to respect climate, orientation and locally produced materials will inform their nature and aesthetic, making them innately part of the landscape – a new vernacular.

This innate recognition of land as a functional element is in fact unique to the Irish territory. There are few similarities, for example, to the British picturesque conception of landscape. In Ireland, historically speaking, the natural landscape has always been a working landscape, cultivated and grazed within a culture of agrarianism. Through a canny appreciation of the Irish vernacular conscience, still prevalent in many parts of Ireland, ‘Hinterland’ can arguably help spatial planners and policy makers better understand the meaning of landscape urbanism and its potential application to the Irish context.

Conclusion

A polarized debate is currently underway in Ireland where one side wants total freedom to develop their land and the other wants an unrealistic adherence to a compact city model. In the midst of this the politicians seem incapable of offering any vision. FKL’s ambitious scenario has attempted to provide an answer to balancing the dilemma of a rural-urban continuum. As a radical proposal, therefore, ‘Hinterland’ can be read more as a valuable exercise in 'designerly' research that could serve to kickstart a debate about where the society is headed with urban generated housing spreading throughout the countryside. By constructing an innovative vision of agricultural productivity and self-sufficiency in the new economy of alternative fuels, the project leaves us with a new frame of reference in the realm of the possible. The best qualities of the Irish landscape – its fertile soil, wet and windy climate – are used as a powerful argument for breathing life into a new super-rural condition. A new emphasis on bio-crop production might forge a change of attitude and understanding of place, but only if stakeholders can be convinced of its potential. By adopting the scenario technique FKL are aware of this:

Scenarios are not predictions. They are stories built around methodically constructed plots; their importance lies in the conversations they spark and the decisions they inform.

Landscape urbanism reasserts a patrimonial learning from the past, which can inform how not to make the mistakes of the future. While contemporary society has lost much of vernacular landscape, the basic human need for survival against the elements, the forces of nature, etc remain the same as always, and is becoming ever more topical in the context of climate change. In this sense it there is a lot than can still be learned from the techniques employed by our ancestors who, by necessity, lived at closer range to the natural elements. The clachan dwellers needed propinquity to the land in order to survive. It may be that some time in the not too distant future we may once again need this propinquity for energy production (albeit of a different type). To what extent this requires us to have closer attachment to the land remains to be seen.

REFERENCES

AALEN, F.H.A: Future of the Irish Rural Landscape, Department of Geography, TCD Dublin, 1985

BANNON, Michael J: “The Irish Settlement System”, in: INT. GEOGRAPHIC UNION (Commission on National Settlement Systems): The National Settlement Systems. Warsaw, 1970, pp 1-39

FKL: “Sub-urban to Super-rural”, in O’TOOLE, Shane (ed): Sub-urban to Super-rural. Ireland at the Venice Biennale 10th International Architecture Exhibition. Dublin. Gandon, 2006, pp. 12-17

McCOURT, Desmond: “The Dynamic Quality of Irish Rural Settlement”, in: BUCHANAN, R.H.,

JONES, Emrys, McCourt, Desmond (eds): Man & His Habitat. Essays Presented to Emyr Estyn Evans. London, Routledge, 1971, pp. 126-164

EVANS, Estyn: The Personality of Ireland. Habitat, Heritage & History. London, Cambridge University Press, 1973

GOTTMANN, Jean: Megalopolis: The urbanized northeastern seaboard of the United States. Cambridge-London, MIT Press, 1964 (Quoted in COAC Forum:Explosió de la Cuidad, Barcelona 2004)

O’TOOLE, Shane (ed): Sub-urban to Super-rural. Ireland at the Venice Biennale 10th International Architecture Exhibition. Dublin. Gandon, 2006

JACKSON, J.B.: “The Vernacular Landscape”, in: PENNING-ROWSELL, E.C. & Lowenthal, David (eds): Landscape, Meaning and Values. London, Allen & Unwin, 1986

JOHNSON, James: “Studies of Irish Rural Settlement”, in: Geographical Review, Vol. 48, No. 4. October, 1958, pp. 554-566

MEITZEN, August: Siedlungen und Agrarwesen der Westgermanen und Ostgermanen, der Kelten, Römer, Finnen und Slawen. Band III: Atlas. Aalen, Scientia, 1963

RUSSELL, Richard Rankin: “‘Something is being eroded’: The agrarian epistemology of Brian Friel’s Translations”, in: New Hibernia Review.10 (2) Summer, 2006. pp. 106-122

SHANNON, Kelly: Rhetorics and realities adressing landscape urbanism : three cities in Vietnam. (Unpublished PhD Thesis. KU Leuven, 2004)

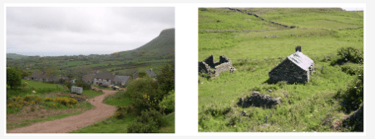

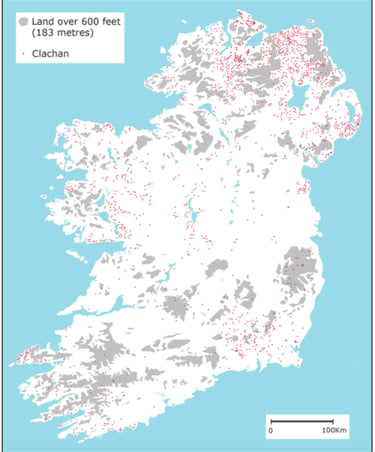

Distribution of clachan settlements in Ireland circa 1900. Map adapted from McCourt (1971)

The concentration in numbers in those parts of the island is partly due to the dislocation of native people following successive periods of colonial invasion from the east. The clachan settlement differed in nature to the ancient English ‘ton’ (McCourt, 1971, p. 132). While the ‘ton’ belonged to a feudal-manorial order, the clachan settlements remained purely as ‘open’ residences of large, extended families, and never developed the critical mass to form villages. As an outgrowth of tribal society, the clachan functioned within a spatial framework of minute territorial divisions. The impact on landscape was one of open fields of intermixed strips and plots whose length, breadth and shape depended on locally varying factors such as soil consistency, topography and technology (McCourt, 1971, p. 131).

The clustering of dwellings was more a pragmatic response to the harsh environment than any conscious decision decreed from above. As Desmond McCourt (1971) notes:

The tendency to live in family clusters instead of isolated farmsteads was largely a response to the high degree of mutual dependence made necessary in Irish agrarian-tenurial practice (…) It was in keeping too with the familistic basis of Irish society according to which the kin group, containing all the relations in the male line of descent for several generations, was the normal unit for owning and inheriting property.

The current discourse of landscape urbanism has arguably been shaped by a desire to understand and appreciate landscape as a means through which order and harmony can be brought through design. The clachan settlement can thus serve as an interesting point of entry into a discussion on what can be learnt from the ancient traditional landscape forms. Reflecting on the meaning and context of the term landscape, J.B. Jackson (1984, 1986) used the term ‘vernacular’ to describe a medieval, unplanned, organic form of settlement in constant flux with nature. He describes this landscape as one where,

Spaces are usually small, irregular in shape, subject to rapid changes in use, in ownership, in dimensions; that the houses, even the villages themselves, grow, shrink, change morphology, change location; that there is always a vast amount of ‘common’ land – waste, pasturage, forest, areas where natural resources are exploited in a piecemeal manner; that its roads arc little more than paths and lanes, never maintained and rarely permanent; finally that the vernacular landscape is a scattering of hamlets and clusters of fields, islands in a sea of waste or wilderness changing from generation to generation, leaving no monuments, only abandonment or signs of renewal.

JB Jackson; Discovering the Vernacular Landscape (1984). Quoted in Shannon (2004, p. 108)

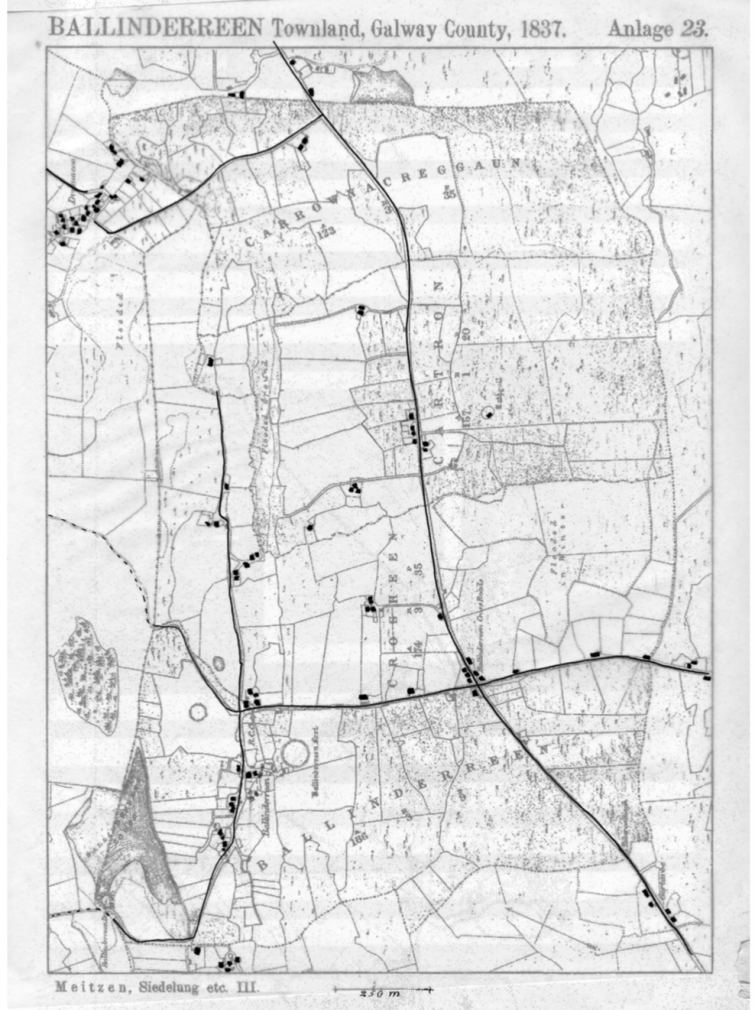

As a pre-modern, organic form of human inhabitation, the clachan can be understood as very much what Jackson had in mind in describing this type of landscape. The clachan settlement would expand and decay with no conceivable plan. There is barely any hint of formality in the arrangement of clachan dwellings. There is no discernable central space to give structure or to anchor the community. There were no courtyards or road crossings that might suggest a reason for choosing to build there. The only justification for the choice of site was the proximity to land that could be cultivated for means of sustenance. In this sense the clachan can be regarded as an ancient form of [unconscious] landscape urbanism: The siting of the houses according to topography; the slope of the land which provided a crucial means of protection against the harsh climate; and a natural drainage system for runoff. The pragmatic use of natural materials of stone and thatched or tiled roofs used to construct the buildings and demarcate field divisions helped the dwellings ‘blend’ with nature. All of these techniques evolved out of a long association and understanding of land as a life-giving element.

Jackson (1986, p. 75) interprets a vernacular landscape as a series of three concentric spaces: a village enclosure, cultivated fields, and a belt of uncultivated land.The farming style associated with the clachan is characteristic of this spatial division, except that the clachan had two types of cultivated field: Infield and outfield. The former might be on a well- drained hillside, and kept in permanent cultivation. The latter was usually at a further distance from the dwellings, of a poorer quality soil, and thus only periodically cultivated. The space between the dwellings was open. Field divisions were usually demarcated using the same materials as the dwellings – dry stones. Beyond the fields the land was common to all inhabitants of the townland (an ancient Irish administrative division ) and without demarcation. Evyns (1973) recognises the innate appreciation of habitat and concept of social cohesion within this system: “[It was] well adapted to the constraints of an uncertain climate and a difficult fragmented environment where good arable land was scarce but rough grazing plentiful in mountain and bog”

As a purely vernacular type the clachan was in a constant state of flux with the landscape, expanding and contracting with the change in family circumstances. The system of land inheritance, where the land would be continually subdivided probably owed much its decline as a viable productive of use, as landholdings would decrease in size until it they were worth nothing. The so-called Rundale system of inheritance was eventually abolished during the British land reforms of the late 19th century.

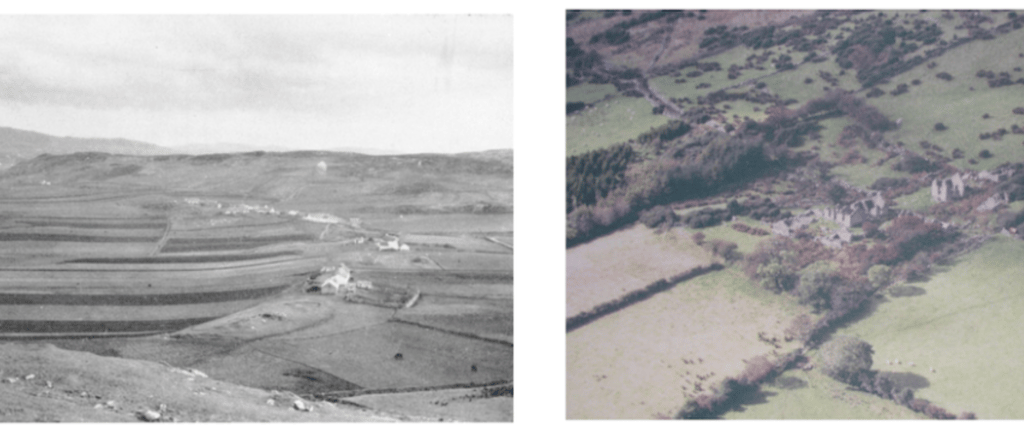

Remnants of Irish clachan settlements

The clachan is an organic form of settlement found in parts of rural Ireland and Scotland, where a cluster of dwellings are located as close as possible to productive farmland. Aalen (1985, p. 61) describes the clachan as a:

Group of small farms and cottages clustered together in an informal manner and lacking shops, a church or any other institutions. The clachans have a striking visual expression, particularly the traditional buildings fitting in to the rocky landscapes and enlivened by whitewash walls, and roofs of slate or thatch.

According to Evans (1973), the Irish clachans have co-existed with the isolated farm dwelling in Ireland since the Iron Age (fourth century BC). Following a period of farming reforms in the late 19th century, clachans became largely extinct, although some relics can still be found in the isolated parts of the northwest and southwest of the country.

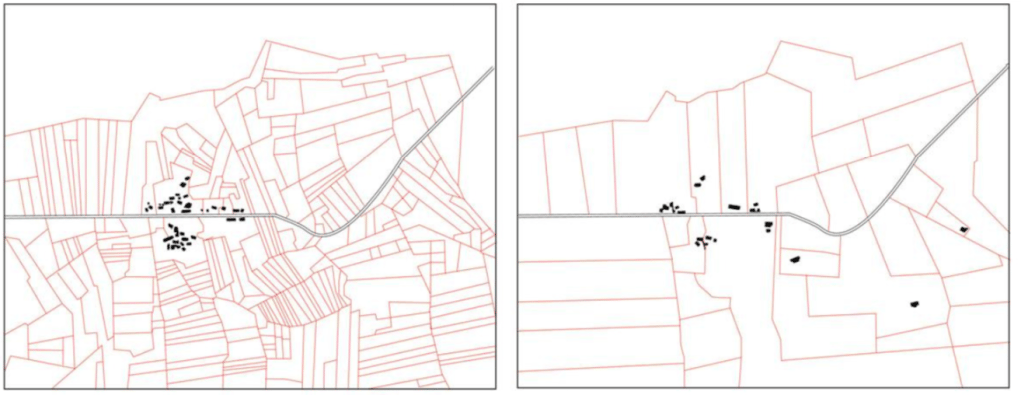

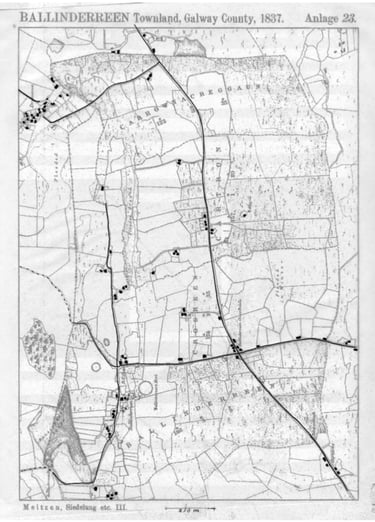

Mapping the decline of clachan settlements after British land reforms: Cloonken, Co. Mayo in 1837 and 1909. Map adapted from Johnson (1958)

Despite its decline something of the vernacular remains in the present day cultural landscape of contemporary Ireland. Irish playwrights have been concerned for many years with the loss of Irish cultural heritage and close association with the landscape as a life-giving entity. Brian Friel, for example, in his play Translations, developed his own well-defined agrarian theory that proposes the continued need for a viable rural farming community in Ireland as a counterweight to the rapid urbanization of the country. Friel’s villagers in Translations display an admirable “harmony between local ways of farming and local ecosystems” as they practice a form of farming that is localized, egalitarian, and communal (Russell 2006). The geographer Desmond McCourt recognised the pervasiveness of the dispersed vernacular settlement type in the cultural imaginary of contemporary Irish society. In his 1971 paper on the Irish rural settlement form, he notes (p. 144) “the consistent pattern of diffusion that runs through the country’s cultural history”, which effects “a regional dichotomy that is still relevant to the present day geography and rural sociology of Ireland”. This present day dichotomy is exacerbated by the prevalence of speculative housing developments that continue to colonise much of the outer urban fringes and into what were previously rural villages.

A ‘snapshot’ of the Irish rural vernacular landscape: Ballindereen Townland, Galway County, 1837. (Source: Transparency overlay. Base map taken from Ordnance Survey 1837 edition (Meitzen, 1969))

Sub-urban to super-rural / Hinterland

We now move to comparing the traditional clachan form with “Hinterland” by FKL Architects; part of an ensemble of scenario projects that were produced for the Irish entry to the Venice Beinnale in 2006 under the title "Suburban to Super-rural". In this hypothetical study, nine different scenarios explore how a more sustainable Ireland might look in 30 years time. The underlying concept of Hinterland is to use the productive potential of the landscape and the imminent energy crisis as the means through which car-dominated sprawl can be transformed into some form of ordered settlement structure. The scenario starts from the hypothesis that a return to agricultural productivity is the logical next step in the context of a sharp increase in the demand for alternative energy sources that imminently awaits us. The structuring elements to limit the settlement are the highly accessible hinterlands of new motorway corridors. Accepting the fact that the majority of investment in transport infrastructure over the next 20 years will be spent on roads, the project makes a case for how this new linear-dispersed settlement can achieve a more sustainable, ecologically balanced and socially cohesive environment. The project tries to subvert the logic that leads to sprawl by requalifying the productive value of agricultural land, thus bringing people closer to the agrarian principles of self-sufficiency and social, economic and ecological cohesiveness.

FKL’s “Hinterland” vision of a Super-Rural (as opposed to sub-urban) landscape. The vision calls for a “reevaluation of the land, and moving away from cash-crop housing towards an evolving productive landscape”, thus enabling a “sustainable interdependence of a repopulated rural hinterland with the road network that connects Ireland’s urban centres”. Source: https://www.fklarchitects.com/hinterland

The authors of Suburban to Super-rural claim that in Irish planning culture personal freedom is often privileged over collective concerns that help drive social cohesion (a fact that is playing out in very unfortunate ways during the current global pandemic), and land has come to be seen as a mere commodity, to be developed in the most profitable way. The resulting sprawl is interpreted as “driven by Ireland’s obsession with the car and an innate desire to live on the land”. It is thus “a uniquely successful product of our national psyche and the free market, reinforced by a lack of infrastructure, coordinated planning, regulation and political will”. As a response the designers aim: “to evolve new living conditions that are not a sub-genre of the urban but rather a hybrid of the best aspects of both rural and urban—a super-rural condition”. Each home generates its own energy needs and farmers supply bio-crops to fuel the transport requirements. Public transport to the larger towns and cities is provided at a ‘hub’, which is easily accessible from all parts of the hinterland by walking (40 minutes), cycling (20 minutes) or by car (5 minutes). A balance between privacy and urban vitality is ensured by the positioning of individual dwellings in a low density network of village-like clusters. The division between public and private land is deliberately blurred and the new productive fields can be used as recreational space.