Participatory Placemaking

An account of participatory placemaking in a planned town near Hangzhou, China. The community planning event took place in 2014.

8 min read

Summary

Following several decades of urban expansion unprecedented in human history, China is on the cusp of a transition from large-scale greenfield planning of new towns and industrial areas to brownfield regeneration and urban renewal in existing towns and cities (ref to gov policies). The transition demands careful thought from planners and policy makers around public participation in the planning process. It can’t be all top-down when you are dealing with existing residents and multiple local stakeholder groups. But what form of public participation is appropriate in the Chinese context? The answer is not clear cut. This post introduces the concept of participatory place-making and a case study of where it was applied in a Chinese context. The post ends with some thoughts about lessons learned and suggestions for planners in China who might wish to adopt this approach.

Background

I had the opportunity to participate in an Chinese urban planning experiment, where we involved members of the public in the planning and design process for the next iteration of a town development plan. The company I worked for was approached by the developer of a new town to conduct a community visioning exercise. Invited community representatives of all ages came together in a town hall style meeting to discuss issues and share ideas about the desired direction of the town. Our team had already completed several successful similar community planning exercises in China (all for private clients). Previous projects had led to positive master planning outcomes. Based on our extensive experience both abroad and within China, the promoters of Liangzhu approached us to help experiment with this type of approach at their town. Our brief was limited to organizing the community planning weekend and preparing a follow-on report. The end result was a report from the community visioning exercise with some recommendations that can be used by stakeholders in Liangzhu for the next iteration of the town’s development plan.

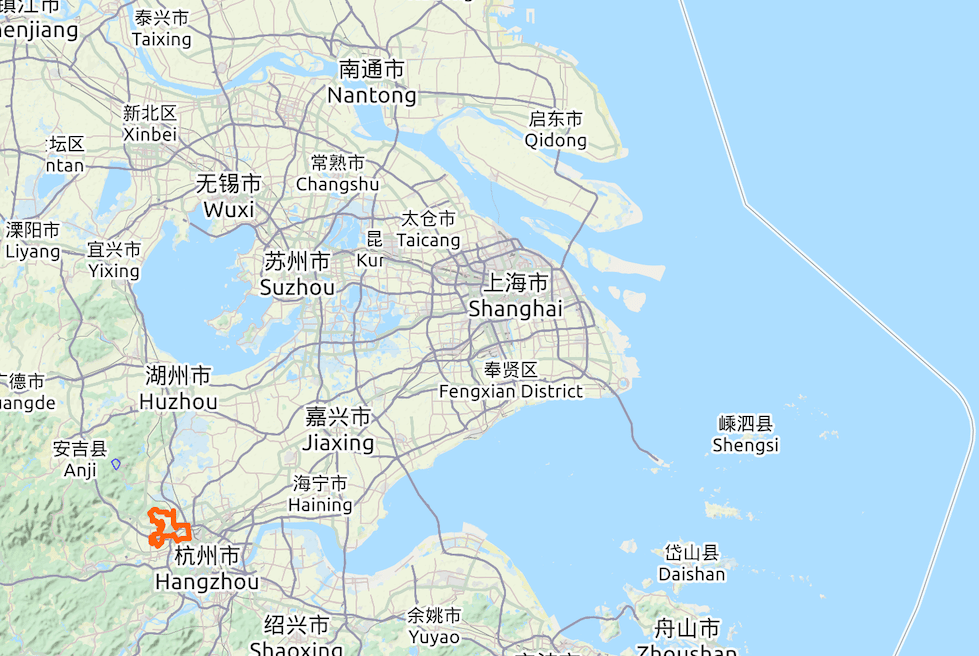

Liangzhu Culture Village - masterplan and surrounding future development area

I define the terms ‘participatory’ and ‘place-making’ to mean an approach to planning that involves local stakeholders – the users of a new place that is being envisioned – and gives them a direct say and role in shaping the vision and plan. Place-making itself can be considered as a holistic and multi-disciplinary approach to the planning, design and management of public spaces. The concept and term has been around in Europe and North America since the 1960s, with writers like Jane Jacobs and William H. Whyte who offered groundbreaking ideas about designing cities that catered to people, not just to cars and shopping centers, after the period of post WWII modernist planning and cheap oil had led to comprehensive suburbanization with highly segregated land uses.

A place-making approach starts with a comprehensive effort to understand the local place and strives to identify what makes somewhere special – be it the existing landscape, local history, culture, etc. The process emphasizes extensive engagement with all types of stakeholders – government, investors / promoters, and locals in a structured forum where there is an attempt to treat everyone as equals as much as possible. The collaborative process encourages mutual understanding, shared ownership & the development of a collective vision between experts and locals. Design proposals are then put forward that respond to the unique opportunities and challenges of the place, drawn from the collaborative planning process, with extensive knowledge built up from a community & stakeholder engagement process.

Involving members of the public directly in the planning and design process is something very familiar to Europeans. There are lots of proven benefits. It facilitates creative problem solving through dialogue between different groups. Empathy and trust can be built amongst disparate community / stakeholders groups. More participation from different groups encourages more diversity of opinion and thinking outside the box; the time spent in the same room face may help to foster a process of reconciliation. Community planning events increases transparency which may reduce the risk of objections and conflict at a later stage. The proposals may be seen to have more legitimacy as community values are represented. Time-bound community and stakeholder workshops can facilitate rapid decision-making when needed; they can also help to ‘demystify’ complex and technical issues; complex problems can be more easily understood by individuals

But there are always caveats. The process may be only loosely defined; public participation is often voluntary and the outcome is not legally binding. Collaboration and charrette process is not a ‘magic bullet’! The process is often just voluntary. It can be time-consuming and requires a learning period for participants. It requires sensitive facilitation and broad community representation to be really effective! In some situations, it may require quick decision-making, and sometimes adequate or sufficient information / data is not readily available at the time the workshop is held.

The case of Liangzhu New Town

Location of Liangzhu, Zhejiang Province; approx. 200km southwest of Shanghai (source: Open Street Map)

Located near Hangzhou City on China’s east coast, Liangzhu is a new town developed as a residential mixed density suburb by one of China’s largest property development firms. It is also a tourism hub, ancient settlement, home to one of China’s most ancient settlements (5,000 years old). Liangzhu’s population is targeted grow up to 45,000 residents by 2022, Covering a total area of about 667 hectares. Among its cultural and social offerings are a museum, church and art gallery by architects of international repute. It also has schools, a five star resort and spa, idyllic residential areas, various public amenities. Notwithstanding its unusual programmatic mix, Liangzhu has been held up in China as a model privately developed town, emphasising the attention given to public facilities, high quality public realm, and promoting a strong civic culture amongst its residents.Like any town, it is not without its own problems, be they conflicts between local residents and tourist visitors, or the uncertainties around longer term management, maintenance and ownership of privately developed public infrastructure – roads, refuse, water supply, wastewater etc.

A village square in Liangzhu

The town itself is only 10 years old. Prior to that it was mostly farmland. In 2000, a real estate group formed an agreement with the local government to undertake a joint development called Liangzhu New Town project. Construction started in 2002. The first housing developments were complete by 2004. In 2008, a Villager's Convention' was signed as an agreement akin to a local code for the residents to abide by. By 2010, Liangzhu had formed into a small town with a community facilities, including a hospital, school, public bus service, Community Cafeteria and Food Street. At the same time, a number of major tourist attractions were also being developed nearby the clusters of residential neighbourhoods, including the Liangzhu National Heritage Park, a 5 star hotel and resort, Liangzhu Museum, Church, Arts and Cultural Centre, some of which were designed by the most famous international architects.

Local village supermarket

The main avenue of the town

My firm was approached by the developer to conduct a community visioning exercise. Invited representatives came together in a town hall style meeting held over two days to discuss issues and share ideas about the desired direction of the town. We had already completed several successful community planning exercises in China (for private clients) and had a strong track record from completing a range of successful projects Europe.

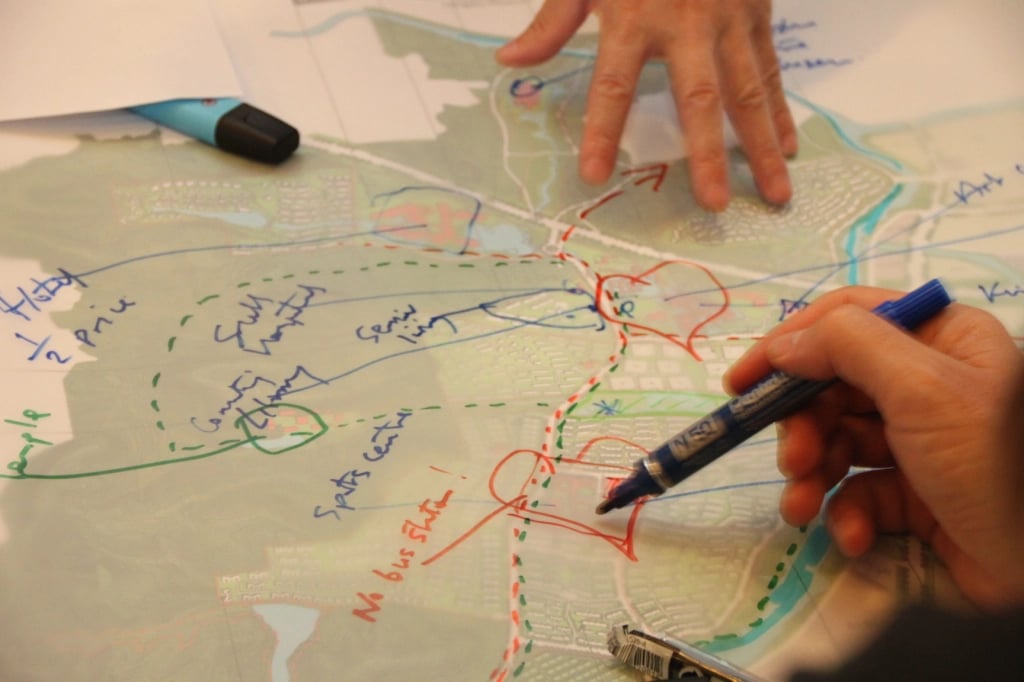

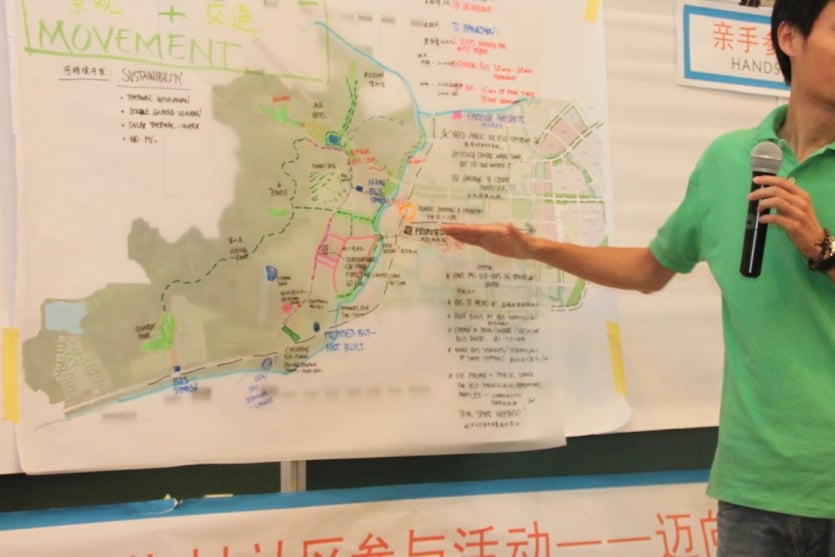

Over the two days, we undertook extensive brainstorming exercises with local stakeholders; identifying problems, dilemmas, areas of conflict; as well as things that are working well. It was an ideas forum with invited representatives of the local community and other key stakeholders and experts.

The lively discussion helped to generate lots of important ideas and raise key issues for the design team. The team was very impressed with the level of sophistication and understanding from the stakeholders and their ability to articulate key issues. We actually observed quite a few similarities between quality of life issues in china and Europe. It was an interesting social study. Participants were given post-it notes to write down their opinions and suggestions on key issues.

The planning team spent most of the time listening and recording information, trying not to influence the flow of discussion too much. Reporting back was done by participants, not facilitators.

At the end of two day workshop, representatives from the community met with the towns promoters and municipal government to discuss the results and agree next steps. We documented these discussions, again bi-lingual, and prepared a report for the client to assist them with the next stage planning. For the next step it was agreed to re-visit the town’s residents charter and to form a committee with representatives from the town’s promoters (real estate developers), the residents and the municipal government to take forward the issues and suggestions to inform the next iteration of the town’s development plan. Given Liangzhu’s unique status as a privately developed town, one of the primary concerns of the residents was to seek clarity on the long term ownership and management of public infrastructure (roads, water, waste etc), which had up until recently, been managed privately, as well as the model for delivering new public facilities such as schools, public transport, etc.

Personal reflections

The experience of Liangzhu, and other similar projects in China has showed us that this form of community engagement in the planning and design process is feasible and can produce positive results, especially in terms of building trust and empathy between stakeholders, as well as stimulating local leadership. In any case, there a few common principles we found that can be applied to most situations to get the most out of experience. For example, we try to treat local people as the experts. The planning team should act only as facilitators. We were there to listen. We tried to build a trustful relationship and create an atmosphere where people were willing to speak out without fear of upsetting the authorities. We attempted to recognise and celebrate the diversity of views. As we explained to the client who sponsored the event, the process was not just about finding information and consensus but also stimulating local leadership and action.

East meets West

Of course every situation is unique and needs to be adapted to suit the local context to stand the best chance of a successful outcome, not to mention the vast cultural differences between east and western culture. Whilst the notion of applying planning techniques that have been developed over decades in Europe and the US to China needs to be heavily caveated, the same principles described in this post can be readily applied, as the case of Liangzhu and others demonstrated. Adaptability is of course very important. As is having key team members who are fully bi-lingual and have spent many years working or being educated in both contexts. Visiting planning experts should have a basic understanding and appreciation of Confucian values, socialism with Chinese characteristics, population control measures, mega-city planning and the rapidly evolving social context, with universal smartphone adoption continuing to fundamentally shift how people live and alter the relationship between the individual and the state. I hope to dig into some of these themes as they relate to urban development in China at a later stage.

It could be said that participatory placemaking in China is still within an experimental phase. I look forward to learning about how the approach is adapted further as China enters into a new phase of mass urban regeneration, brownfield re-development and adaptive re-use of existing buildings, spaces and public infrastructure.